This is an edited version of James Hyman's speech delivered at the book launch for Edith Tudor Hart, Karl Marx Memorial Library, Clerkenwell, London, 2 July 2025.

Hello, everybody. I want to start by thanking you, Graeme (Farnell), for this opportunity to speak about the Centre for British Photography. And first of all, I'd like to congratulate you on your publishing plans. We all know it's a terrific list that is being built up, and I think it's a unique voice in British photography right now. I think it's so important that you're looking at neglected and marginalised figures and seeking to make better-known work that has fallen from view. And that's a shared mission.

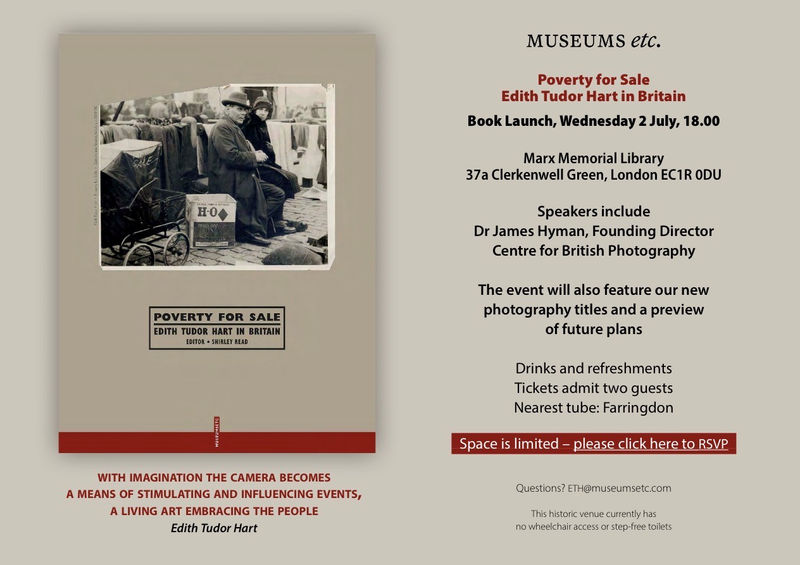

I'm delighted to have worked with you, Graeme, but also you, Shirley (Reid), on the Edith Tudor Hart book. I was excited to write something for it, although it took me a little bit of time to work out what! But I was very pleased to be asked. For me, when I champion photography, I've got a kind of obsession with the actual object: that these aren't just things that can be reproduced and consumed on Google Images, but they have a material presence in the real world. So the essay that I did was about one of Edith's few surviving vintage prints and the writing that she did on the back of it that told the story behind the print. So it was great to be able to do that.

I'm also pleased to have worked with Graeme on the book that he just mentioned on Jo Spence and Terry Dennett. I'm hoping there might be a copy here, but I don't know if there is. I haven't seen it myself yet. I'm looking forward to seeing it! We're also working on other plans for books, we're discussing further collaboration, which I'm excited by. So I'm impressed with what Graeme is doing and excited to be a small part of it.

Now, today, Graeme's kindly asked me to say something about the Centre for British Photography. I want to say a little bit about our motivation and my vision behind what we're trying to achieve. The first thing to say is that the charity was one that I founded with my wife, Claire. And in terms of the collection that we've built up and the charity that we've founded, it's very much something we work on together. Even though I tend to be the one standing up here talking about it! We're a public charity. We have seven trustees, all with strong, individual voices. We had, as many of you may have seen, a premises in Jermyn Street. We set up a gallery space on three floors. I think we produced about 19 exhibitions there. And the intention was always that it would be a temporary space as a proof of concept.

What we wanted to do was excite people, demonstrate the kinds of shows we could put on, the audience we'd have for them, the press coverage, and the buy-in from the photography community that we're trying to serve. We're now using that as a tangible way of fundraising for a permanent home, because otherwise it's a kind of abstract dream. This way we could demonstrate that there actually was a demand for it. But it's obviously quite painful to fundraise at a time when the Arts Council is starved of funds and agendas have also changed. It's not so much about London but the regions. I think that's very important, but support for the regions should not be at the expense of London. It's always going to be at the expense of London if the Arts Council isn't properly funded. So it's a dilemma. We want to create a permanent home, whether it's a museum or a kunstverein, but it really depends on the Arts Council and multiple other supporters getting on board because whilst we've seen funded it, it's not sustainable without others. So a lot of my time now is on fundraising.

But I should mention that we're also staging touring exhibitions. We did two not long ago at Belfast Exposed. We lend a lot. We were one of the biggest lenders to the Tate Gallery show on British photography in the 80s. I think we lent nearly 40 pictures to that. We are really, really keen that the work is seen and, as I say, not just seen in reproduction or on Google Images. We are, though, very unusual as a private collection in that we've put a huge percentage of what we've got online. So if you go to hymancollection.org, you'll see that we've tried to use the collection as an educational resource. If you want to find out more about the diversity of British photography, it's a place to go to.

I should say also that our vision for British photography is not some kind of post-Brexit checking of people's passports. We're actually the opposite in the way that we're celebrating what is happening in this country. We are looking at what is happening here and trying to support it irrespective of nationality. And actually we're trying to celebrate the diversity of voices, showcase different stories. You know, it's genuinely about multi-culturalism. That is our vision.

So that space in Jermyn Street was a proof of concept and if you want to look at the history of it and what we're now trying to do, for example, our expanding grants programmes for photographers, you can find that on the britishphotography.org website. And I should say that each year we also do an annual grants program, and that's to support artists to complete work. So it's to realise work that's already in development. It's not a competition as such. It's not about, you know, submitting a work. It's really about helping photographers realize their projects. And we're hoping to expand that next year and probably increase the amount of money that we award. We have a particular interest in supporting women in photography and celebrating diversity.

We're also unusual in that we cover 120 years of photography and that the collection spans everything from documentary to conceptual work. Yes, we've got an historical collection but we are also very engaged in what young artists are doing today. So, for example, we bought a series of work by Arpita Shah. We've shown that in Belfast, in Oxford, and at the Centre of British photography. And I had a meeting today with another venue that wants to take the show. So we're very much trying to get these voices heard and to give them a platform. Arpita's work is about South Asian women and their experience in this country; their pride in their heritage but also their sense of being British. Pride in that dual identity.

We're also acquiring archives. So we now have the almost complete archive of colour work by Wolfgang Suschitzky, which complements the major archive of his black and white work that is at Fotohof in Salzburg. We have big archives of John Blakemore and Simon Marsden. We are acquiring the photographic archive of artist and activist Caroline Coon. We have a lot of material on Kurt Hutton. That archive side is very important because it's about the preservation of the material, but also in many cases about access through the digitizing and photographing of it. So with Suschitzky, for example, there are thousands of colour works that have never been printed or scanned. So we've spent the last 9 or 10 months with one particular body of that work getting it scanned and then cleaned up. We hope to do a publication of that, for example.

But today I really want to speak in a personal capacity, not as an official spokesman for the charity, despite being its founding director. I want to say something personal about what motivates me, what my vision is and what has brought me to this point.

My academic background complements what Graeme is trying to do. My doctorate was on art and politics in the Cold War looking at the period from 1945 to 1960 - if any of you want to read a doctorate, The Battle for Realism was published by Yale University Press. So it is out there.

I was very interested, particularly, in the position of John Berger and the way that he looked at art and society and attempted to make a connection between the artist and audience. I think that a lot of what he wrote in the 1940s and 1950s remains important for us today. I spent literally years in Senate House going through microfilm and going through old issues of the New Statesman as nothing was yet digitized. I absolutely immersed myself in what Berger was writing. And really, in many ways, the kind of issues he was looking at has been a platform for everything I've done since. In his early work, Berger was talking about direct communication. He wanted art to be accessible to everyone. He was fighting against elitism or obscurity. He felt that a Jackson Pollock was self-indulgent. Essentially, he was more interested in work that would communicate with as wider public as possible. And for me, that education side is very important. You can as, an artist, try and do work that communicates but the educational function, of a website or a wall text, is also absolutely crucial. And one of the great achievements at Jermyn Street, at the Centre for British Photography, was not just the size of the audience, but also that it was all ages and also incredibly diverse. People felt it was for them. And I'm very proud that the exhibitions we put on did communicate to such a broad audience.

John Berger was anti-elitist. He was for access for all, he was for inclusion. And we seek to celebrate that as well. The idea of amplifying multiple voices, opinions, stories and histories. Importantly, listening and learning from those with different and even opposing views.

To go back a step, we founded the charity just before the Covid pandemic. And I think that's significant. It was post-Brexit. And I've explained why I think that, in a way, we're an antidote to the insularity and xenophobia often associated with Brexit. But Covid, for me, was a kind of world-changing moment in the way that it radicalized people. I think that we all spent too much time on our phones, on social media, susceptible to it's algorithms, and increasingly immersed in its extreme content designed to fire us up and keep us on the platform. They became echo chambers in which more and more extreme views were encouraged, reinforced and entrenched. And simplistic sloganeering now transforms complex situations into comforting certainties.

I think this has had a profound effect on the world. And it's too little written about or acknowledged. I think the world has become an angrier, more polarised, place. It's less kind, less tolerant, less understanding, less safe, less curious, less open. It sometimes seems that we would rather deplatform someone whose views we don't share rather than attempt to listen and learn or engage and persuade. A world of cancel culture. A world in which discourse has become about winning not learning. This is a strategy that increases division - without engagement there is no learning and without learning there is no growth.

I think part of my vision is to try and see what we can do to counter that anger, explicitly and implicitly. One of the things that I'm interested in is learning from others and that's one of the reasons why I'm so concerned about this kind of echo chamber world that so many of us are now living in. Openness to new, different or challenging ideas is being lost. I genuinely want to listen to different voices and learn from different opinions, not shut them down. I don't just want to listen to those with whom I already agree and cancel those whose opinions I dislike. My views are not fixed.

When I wrote my doctorate, The Battle for Realism, I concluded by looking at what we could learn from each side of the battle. This sort of approach is becoming anathema. And part of the problem is our political system. Our political system is about winning. It's adversarial. It's about the winning argument, not the best solution, not taking the best from wherever it might come. It's like debating. Debating is an extreme example where you can toss a coin to decide which side you're going to represent. It's not about a principled, value-driven position. And I feel that a lot of the time now discourse is about trying to win an argument, not trying to understand the other person, or come up with an informed position. The reduction of complexity to sound bite. I think this is a real failing in today's society. We are becoming more and more extreme, more and more dogmatic, and less and less willing to see other perspectives. So I think in a way, what I'm trying to do - and I don't want to sound overly idealistic or romantic or soppy - is to do things from a place of love at a time when there's so much hate.

It's about a love of art, a love for creators, a love for community, a love of learning - I'm always fascinated when I discover a new artist and then try and read and read and read and find out more - a love of communication. Above all a love for others. And I think this is what drives me. I want to create a warm, nurturing environment that counters division. To champion a plurality of views; the toleration of others; respect for those that we disagree with; listening; growth. I want to prioritise lived experience, not received opinions, and to celebrate different histories, cultures, narratives, and opinions.

I feel that in the angry world that we live in today, this is needed more than ever. And that's why I say, although we founded the charity before the pandemic, it feels in some ways that it's even it's more urgent and necessary now because there has been a shift in the world.

We rightly pride ourselves on our compassion and our common humanity. And we call out homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, racism and misogyny. And that's why for me, watching what happened at Glastonbury a few days ago was so chilling. Whatever one's politics, a crowd joining in calls for the death of anyone is something that should pain us all. It's impossible to square the circle of sensitive and compassionate people thinking they are on a moral high-ground when they are chanting for people's death…..

….. I think we should be much more robust and muscular in challenging such extremism, at home as well as abroad, and much stronger in celebrating our values. Shame about our past should not lead us to turn away from condemning behaviours in others that we would not tolerate in our ourselves. So, whilst celebrating the benefits of multi-culturalism and championing the rights of others, we should also be stronger in championing our own values, values such as moderation, diversity, pluralism, consensus-building, tolerance, respect and freedom. We should be vigorous in challenging threats to these values wherever they may come from, even when it comes from those we might otherwise support. We should be actively combatting extremism, countering anger with compassion, listening to others, and bringing out each other's innate kindness.

So the Centre is an ideal not just a place. It aims to be a safe space, somewhere that is supportive and inclusive based on respect for each other. I want to create somewhere that is welcoming and open. A place where, whether it's bricks and mortar or virtual or conceptual, we can learn more about others and about ourselves. Somewhere that different perspectives can be shared as well as challenged without fear of cancellation, a hub that brings together people of goodwill, a place that seeks to enhance what unites us.

Without such initiatives, we will lose the freedoms that we take for granted as our society continues its lurch towards extremism and the seduction of slogans and easy solutions. In my adult lifetime, this has never seemed more urgent.

Thank you.